Technology

Software industry 2023: Profit is taking center stage - A change of mindset for software companies

The pressure from Wall Street is leading to a shift away from growth at any cost. Companies like Salesforce and Box are improving their operating margins in this context.

Wall Street pressure reduces focus on growth at any cost. Salesforce and Box among the companies improving their profit margins. Over the last ten years, software companies only focused on growing as fast as possible. That changed in 2023. Profit and operating margin became the buzzwords of the industry. With rising interest rates and companies cutting their IT budgets, selling computer applications seemed less like an inexhaustible source of expansion.

Investors had enough of the growth-at-all-costs mentality that has dominated the software industry since the financial crisis. Management teams responded with layoffs, outsourcing of work, cutting benefits, closing offices, ending speculative projects, and scrutinizing their own software budgets. In general, they tried to replace cultures of abundance with frugality. According to an analysis by Bloomberg, discussions about profits were mentioned twice as often in transcripts of earnings conferences, corporate events, and other presentations compared to 2019.

In comparison, references to "growth" and "revenue" increased in this period at less than half the pace. "The new trend at the moment is to talk about operating margin," said Guy Melamed, Chief Financial Officer at Varonis Systems Inc., during an earnings conference in May. The pressure was particularly strong for companies that were experiencing losses. Twilio Inc., which produces communication software, conducted three rounds of layoffs and eliminated benefits such as sabbaticals and book allowances.

The company is expected to achieve its first significant adjusted earnings per share this year. Snowflake Inc., Okta Inc., and Nutanix Inc. are other companies that will record their first major annual profit in 2023. Box Inc. recorded its first positive operating margin. The most significant change in emphasis occurred with Salesforce Inc., which is often seen as an industry leader.

Given the slow revenue growth, a group of activist investors called on the company - valued at around $150 billion at the time - to stop burning money like a startup and to increase margins to the level of Adobe Inc. and Oracle Corp. Many believed that highly visible marketing initiatives, such as the Dreamforce conference in San Francisco, were the source of Salesforce's excessive spending.

In reality, the biggest problem was the compensation for the massive team of salesmen. In addition to the largest layoffs of all time, Salesforce has been working to bundle its products and sell them through new channels such as the cloud unit of Amazon.com Inc., Amazon Web Services, and self-service pages to spend less on commissions. Workday Inc. and HubSpot Inc. also discussed reducing sales and marketing costs. This line of costs is often the largest for enterprise technology companies that rely on armies of sales representatives to explain why their peculiar products are necessary.

Many companies hired research and development talents from abroad on the development side to pay lower salaries. ServiceNow Inc., Appian Corp., PTC Inc., and LiveRamp Holdings Inc. each spoke about cost savings through hiring developers in India. C3.ai Inc. spoke about higher margins through a new research center in Guadalajara, Mexico, while Box mentioned hiring more engineers in Poland.

The changes led to an increase in margins for many companies that had previously paid little attention to this metric. According to Rishi Jaluria, an analyst at RBC Capital Markets, the iShares software ETF, which is often seen as an industry benchmark, has risen by about 60% this year, mainly due to higher profits and excitement surrounding generative artificial intelligence. For the future, the question arises as to whether some companies have invested enough in new growth drivers to increase their margins and may suffer from a lack of growth in the future, according to Jaluria.

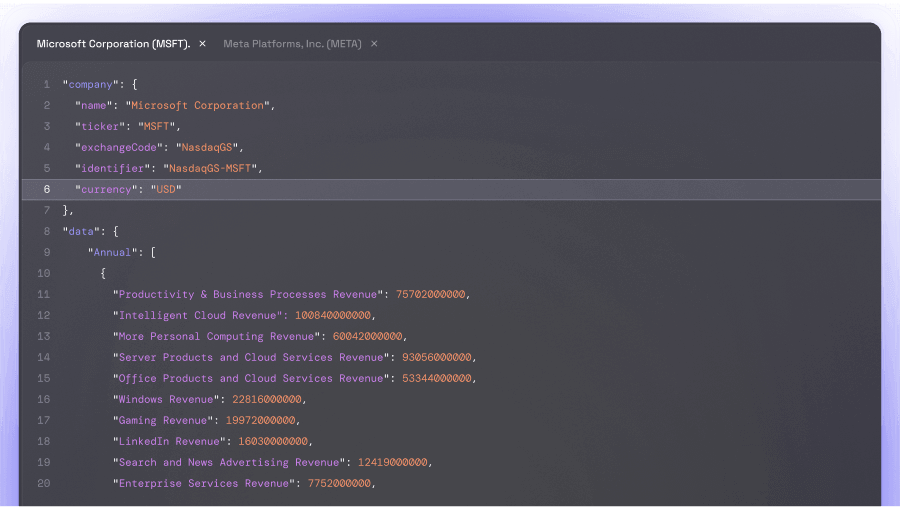

Companies like Microsoft Corp. and Adobe, mature companies with already high profitability, stated that they are investing heavily in new artificial intelligence capabilities and have managed to maintain their margins. Microsoft invested $13 billion in OpenAI, the manufacturer of ChatGPT. Speculative bets were abandoned in the name of major growth drivers - Adobe put its competing product XD on ice, while Microsoft downsized the teams behind hardware devices like augmented reality glasses.

"We really focus on ensuring that every dollar we spend goes back to the priorities we have discussed, namely leadership in the commercial cloud and leadership in artificial intelligence," said Amy Hood, Chief Financial Officer of Microsoft, during an earnings conference in October.

A remarkable exception to this trend was Oracle, whose margins have decreased while the company built its cloud infrastructure services and integrated the acquired company for electronic health records, Cerner. CEO Safra Catz is working to shift the legacy software business to the cloud and bring profitability to "Oracle level". The struggle in the tech industry this year has hit start-ups particularly hard, as these new and often unprofitable companies could become giants for enterprises in the future.

An unprecedented number of them collapsed in 2023, partially due to difficulties in raising funds, as shown by data from investment management company Carta Inc. Some sold at fire-sale prices. Video-conferencing start-up Loom had two rounds of layoffs and was sold to Atlassian Corp. in October for $975 million – significantly less than its previous valuation of $1.53 billion.

Many on Wall Street expect IT spending to increase in the coming year as interest rates decline and demand for artificial intelligence continues to grow. The focus on profits this year has altered the mindset of many company leadership teams, but it is possible that the pendulum could swing back towards growth-at-any-cost, according to RBC analyst Jaluria. "In two years, we could find ourselves back in a growth-at-any-cost cycle."