When Size Becomes a Risk – How Index Giants Distort Shareholder Democracy

Index funds like BlackRock distort shareholder votes, as their portfolio systematics divide loyalties and challenge traditional governance principles.

Shareholder Votes Were Long Considered a Ritual Without Great Influence. With the Rise of Institutional Investors Like BlackRock, This Changed: Fund Managers Used Their Voting Rights to Discipline Boards and Influence Strategic Decisions. But Now There is Growing Concern That These Same Institutions, Due to Their Sheer Size, Are Disrupting the System's Balance.

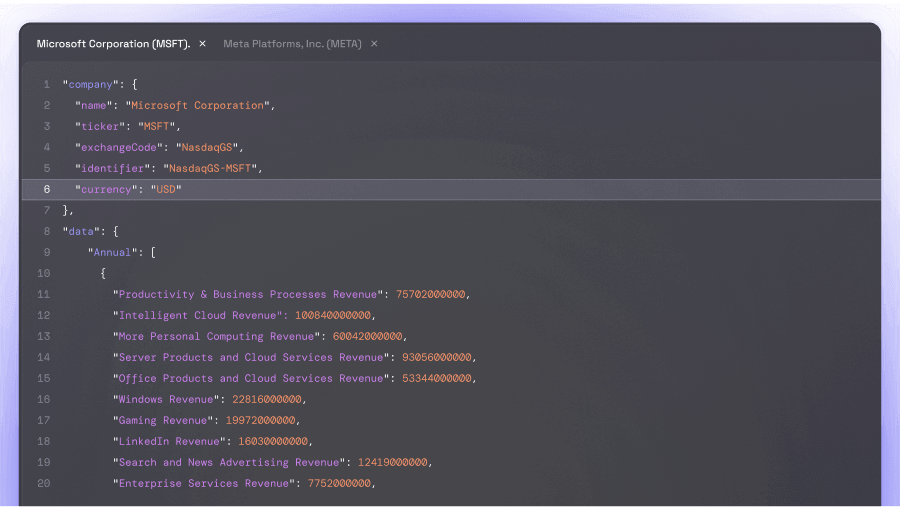

An analysis by Henry Hu and Lawrence Hamermesh, both former top lawyers at the US Securities and Exchange Commission SEC, reveals the weaknesses. They warn of "miscounts, distortions, and unjustified shifts in voting rights" - the current rules are no longer able to keep up with reality. This is especially evident in Delaware, where most US companies are registered and whose corporate law has a global signaling effect.

The problem of decoupling economic interest and voting rights is not new. Already in the 2000s, hedge funds used derivatives to secure voting rights without bearing economic risk. Legendary is the case of Perry Corp, which took influence at Mylan while simultaneously betting that the pharmaceutical company would pay too much for another Perry investment.

Today, conflicts of interest arise systematically without investors having to consciously cause them. Giants like Vanguard, State Street, or BlackRock hold shares in almost all publicly traded companies. In mergers, they effectively sit on both sides of the table. A study from 2022, which examined nearly 2000 M&A transactions, found that investors regularly supported deals that harmed individual companies but benefited their overall portfolio.

The governance debate is thus stuck in a dilemma. If voting rights of large funds were generally classified as biased, smaller activists would gain disproportionate influence. If everything remains as it is, shareholder votes lose their credibility – benefiting those who have long been agitating against the influence of institutional investors, from founding figures to politicians.

The fact that even in Delaware, the mecca of US corporate law, serious discussions about rule adjustments are taking place shows the urgency. And even if the debate is conducted there: The question of whether the principle of "one shareholder, one vote" still holds in times of global index funds now concerns all major capital markets.